Electroacupuncture for Reproductive Hormone Levels in Patients with Diminished Ovarian Reserve: a Prospective Observational Study

Yang Wang1, Yanhong Li2, Ruixue Chen2, Xiaoming Cui1, Jinna Yu1, Zhishun Liu1*

(1Acupuncture Department, Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing 100053, China; 2 Gynecology Department, Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing 100053, China)

Abstract: Background: Effective methods for the treatment of reproductive dysfunction are limited. Previous studies have reported acupuncture can modulate female hormone levels, improve menstrual disorders, alleviate depression and improve pregnancy rates. However, studies of acupuncture for diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) are lacking. This prospective observational study aimed to assess the effect of electroacupuncture (EA) on the reproductive hormone levels of DOR patients seeking fertility support. Methods: Eligible DOR patients received EA for 12 weeks: five times per week for 4 weeks followed by three times per week for 8 weeks. The primary outcome was change in mean follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level at week 12. Mean luteinising hormone (LH) and serum oestradiol (E2) levels, FSH/LH ratios and symptom scale scores were simultaneously observed. Results: Twenty-one DOR patients were included in the final analysis. Mean FSH levels fell from 19.33±9.47 mIU/ml at baseline to 10.58±6.34 mIU/ml at week 12 and 11.25±6.68 mIU/ml at week 24. Change in mean FSH from baseline were -8.75±11.13 mIU/ml at week 12 (p=0.002) and -7.78±9.52 mIU/ml at week 24 (p=0.001). Mean E2 and LH levels, FSH/LH ratios and irritability scores were improved at week 12 and/or 24. Approximately 30% patients reported subjective increases in menstrual volume after treatment. Conclusion: EA may modulate reproductive hormone levels and its effects appear to persist for at least 12 weeks after treatment with no significant side effects. EA may improve the ovarian reserve of patients with DOR, though further research is needed.

Key words: acupuncture, prospective observational study, diminished ovarian reserve

电针对卵巢储备功能低下患者生殖激素的影响:前瞻性观察性研究

王 扬1,李艳红2,陈瑞雪2,崔晓鸣1,于金娜1,刘志顺1*

(1 中国中医科学院广安门医院针灸科,北京 100053;2 中国中医科学院广安门医院妇科,北京 100053)

摘要:背景:不孕的有效治疗方法十分有限,现有研究表明针刺可以调节女性激素水平,改善月经失调,缓解抑郁情绪并提高怀孕率。但针刺改善卵巢储备功能低下的研究还数量相对较少。目的:开展一项观察性研究,旨在评估电针改善卵巢储备功能低下导致的不孕患者生殖激素水平的有效性。方法:合格的卵巢储备功能低下患者将接受12周电针治疗:前4周每周5次,后8周每周3次。主要结局指标为12周时FSH较基线变化的均值。次要指标为LH、E2、FSH/LH比值较基线变化的均值。结果:21名患者被纳入统计分析。所有受试者在基线和12周和24周时的FSH水平分别为19.33±9.47 mIU/mL 、10.58 ±6.34 mIU/mL 和11.25±6.68 mIU/mL 。12周和24周时FSH水平较基线变化的均值分别为−8.75±11.13 mIU/mL ( p=0.002) 和 −8.08±9.56 mIU/mL (p=0.001)。24周时,E2水平、LH水平、FSH/LH比值和易怒评分也较基线明显改善。30%患者月经量较前增加。结论:电针可能对生殖激素有调节作用,这一作用至少可以持续到治疗结束后12周,且安全无副作用。电针可能改善卵巢储备功能低下患者的卵巢功能,但还需进一步研究证实。

关键词:针灸;前瞻性观察性研究;卵巢储备功能低下

1 INTRODUCTION

Diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) is a manifestation of ovarian ageing. As women increasingly delay childbearing, DOR is becoming a more significant challenge for providers of assisted reproductive technology 1. Studies have shown that DOR is diagnosed in 10% of women undergoing investigation for subfertility2. DOR may also have adverse implications for a woman’s wellbeing beyond her reproductive concerns. Changes in ovarian hormones, concomitant with DOR, can cause accelerated bone turnover, low bone mineral density (BMD), sexual dissatisfaction, and disturbed sleep3-5. Involuntary childlessness can also cause significant distress 6.

In Western countries, DOR is usually diagnosed in reproductive medicine centres. Currently, effective methods for improving ovarian reserve are limited. Various treatment regimens and therapies have been reported to improve ovarian response and pregnancy rates during in vitro fertilisation (IVF), but none stands out as superior compared to the others7-8. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation may improve pregnancy rates in women with DOR, but more evidence is required9. In China, DOR patients often choose alternative therapy approaches, such as herbs and acupuncture. Acupuncture may help patients regain regular menses, alleviate depression, and improve pregnancy rates and quality of life10.

To our knowledge, however, there is no existing literature on the potential role of acupuncture specifically for DOR. There are, nonetheless, three published case series studies and one low quality randomised controlled trial (RCT) of acupuncture for the related condition of primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). Two case studies found that electroacupuncture (EA) decreased serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) levels, increased serum oestradiol (E2) levels, relieved anxiety, reduced mental stress and improved menopausal symptoms11-12, whilst the third simply reported that hormone levels were improved in 9 out of 15 patients without providing specific data 13. The single RCT14 randomised 151 patients to receive acupuncture (n=76) or clomiphene and diethylstilboestrol (n=75) for a total of 6 months, without explicitly disclosing the inclusion/exclusion criteria or methods of randomisation and allocation concealment. Menstrual symptoms, hot flushes and levels of FSH and E2 were improved at 6, 7 and 9 months. Although the conclusions of these studies in POI are encouraging, they are limited by poor design, and cannot be directly extrapolated to DOR, which differs from POI in several respects15.

The aim of this prospective observational study was to investigate the effects of EA on markers of ovarian reserve in patients with DOR seeking fertility support, and to also consider its safety.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

This was a prospective observational study conducted from January 2014 to August 2015 in the Acupuncture Department of Guang’anmen Hospital. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Review Board and Ethics Committee of Guang’anmen Hospital (reference no. 2014EC097). It was also retrospectively registered in the National Institutes of Health clinical trials registry at https://clinicaltrials.gov (reference no. NCT02229604).

2.2 Participants

Patients with DOR were recruited by posters at our hospital and advertisements on the hospital website. The main criterion for inclusion was a diagnosis of DOR, defined as a two-fold elevation in FSH level (≥10 mIU/ml but < 40 mIU/ml) in a woman under the age of 4016. Patients were excluded if they: (1) had undergone oopherectomy; (2) had a past history of cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (3) had a current infection or tumour history of the genital tract; (4) had an autoimmune disease; or (5) were amenorrhoeic due to reproductive abnormality or pregnancy. Patients were also excluded if they had taken any immunosuppressive agents in the past 6 months, had accepted hormone therapy/herbs in the preceding month, or could not adhere to treatment for personal reasons. Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

2.3 Electroacupuncture

Standardised acupuncture treatment was provided using two alternating formulae: A (BL33) and B (ST25, Zigong, and CV4). In formula A, stainless steel Huatuo brand needles (diameter 0.30 mm, length 40–75 mm, Suzhou Medical Appliances, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China) were inserted bilaterally into the third posterior sacral foramina (at BL33) and angled inwards and downwards at 30–45° to a depth of 50–60 mm. An EA stimulator (model GB6805-2, Huayi Medical Supply & Equipment Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China) was used to deliver a dilatational wave (pulse width 0.5ms) at 2/15 Hz frequency (alternating at 1.5s intervals) and 0.1–1.0 mA intensity. In formula B, needles were quickly inserted vertically through the skin bilaterally at ST25 and Zigong, and at CV4. They were then slowly advanced vertically through the layer of fatty tissue and into the muscles of the abdominal wall. The needle was stopped when there was resistance on its tip and the participant felt a sting. Needles at left and right Zigong and ST25, respectively, were paired for EA (using the same parameters). The two formulae were alternated. Each EA session lasted for 20 minutes, and patients underwent five sessions per week for the first 4 weeks and three sessions per week thereafter (44 sessions in total over 12 weeks). If participants did not want to be needled during menstruation, treatment and outcome assessment were postponed slightly.

2.4 Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the change from baseline in the mean FSH level at week 12. Secondary outcomes included changes in FSH/LH ratio, mean LH, E2, and FSH levels and a four-point symptom scale (measuring irritability and depression) at weeks 4, 8, 12 and 24 (0 = not at all, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). Patients scored themselves according to their own feelings.

The proportion of participants with a subjective improvement in menses at week 12 and 24 was simultaneously recorded. Patients reported both menstrual cycle length and blood loss, calculated based the number of sanitary pads used and the estimated volume of blood on the pads. A native-brand sanitary pad was used, for which about 5ml blood dyed half of the backside of the pad.

Participants underwent an initial 2-week baseline assessment of menstruation and measurement of symptom scale and serum hormone levels, namely FSH, LH and E2, using ARCHITECT chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay reagent kits (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA). This was repeated immediately following EA treatment at 12 weeks. A further follow-up visit was performed in the clinic or by email/telephone (for those unable to reattend) at 24 weeks. As reproductive hormone levels vary throughout the menstrual cycle, hormone tests were performed on day 2 or 3 of the cycle.

During treatment and follow-up, any adverse events and acupuncture-related side effects, such as fainting, haematoma, severe pain and local infection, were recorded.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The paired t test and Wilcoxon’s Sign Rank test were used for continuous and categorical data, respectively, in order to compare outcomes before and after acupuncture treatment. All analyses were two-sided, and the level of significance was set at p<0.05.

3 RESULTS

From January 2014 to August 2015, 40 subfertile patients with DOR attending our clinic were screened. After excluding patients who were taking hormone therapy or DHEA, or who could not undergo acupuncture treatments on time, 31 eligible patients signed the informed consent form. Of these, six patients didn’t attend clinical visits on time and were contacted by phone. All six patients failed to undergo blood tests when scheduled (two in the treatment period and four in the follow-up period, with greater than one month’s delay) for personal reasons. An additional four patients withdrew from the study because they became pregnant (two by natural conception and two by IVF). Therefore, a total of 21 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study

3.1Baseline characteristics

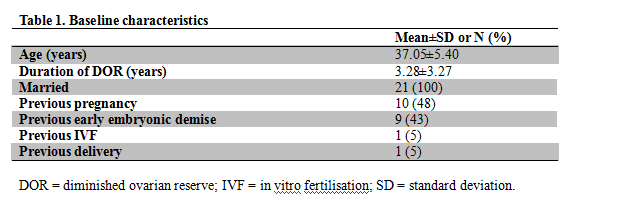

The baseline characteristics of the 21 patients are shown in Table 1. Seven patients had used hormone therapy or DHEA in the past and seven had tried herbs, however none had previously used acupuncture for DOR. One patient had undergone IVF and failed and all 21 planned a future pregnancy. All patients met the inclusion criteria with none of the exclusion criteria at the time they signed the informed consent form.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

3.2 Reproductive hormones

Mean FSH levels fell over the course of the study from 19.33±9.47 mIU/ml at baseline to 10.58±6.34 mIU/ml at week 12 and 11.25±6.68 mIU/ml at week 24 (Figure 2). The change in FSH compared with baseline (primary outcome) was -8.75±11.13 mIU/ml at week 12 (p=0.002) and -8.08±9.65 mIU/ml at week 24 (p=0.001), respectively. Meanwhile, mean LH levels decreased more gradually from 6.35±3.40 mIU/ml at baseline to 4.55±3.47 mIU/ml at week 12 (p=0.062) and 4.33±2.04 mIU/ml at week 24 (p=0.004). Furthermore, we found that the FSH/LH ratio was significantly reduced compared with baseline (3.43±0.32) at week 24 (2.70±0.42, p=0.017) but not at week 12 (3.26±2.84, p=0.274). In addition, mean E2 levels were significantly higher than at baseline (39.16±7.47) at week 12 (96.73±30.72, p=0.016) but not at week 24 (63.16±92.50 mIU/ml, P=0.052).

Figure 2

Serial measurements of serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH), measured by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay, over a 24 weeks period in 21 women with diminished ovarian reserve receiving a 12-week course of electroacupuncture treatment. ** p<0.01 (compared with baseline)

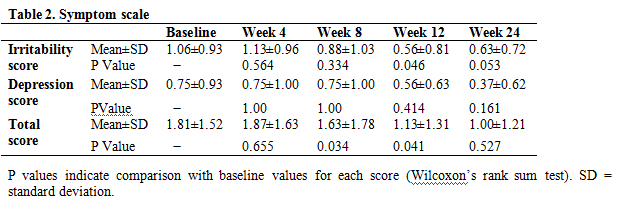

3.3 Symptom scale

Table 2 shows serial changes in the symptom scale, which consisted of irritability and depression. For the total score and irritability subscores, significant differences were demonstrated at weeks 12 and 24 compared with baseline. By contrast, no difference was observed for the depression subscore at any time point compared to baseline. There were no significance differences in total score or irritability subscore between weeks 12 and 24 (p>0.05).

3.4 Menstruation

None of the 21 patients had amenorrhoea at baseline. The mean cycle length was 27.2±3.45 days and blood loss was 34.38±16.21ml at baseline. The corresponding values at week 12 (29.53±5.19 days and 36.25±9.03 ml) and 24 (28.25±3.75 days and 35.63±9.29 ml) were not significantly different compared with baseline. Seven patients (33.3%) and six patients (28.6%), respectively reported a subjective increase in the volume of menstrual blood loss at 12 weeks and 24 weeks.

3.5 Safety

In this study, abdominal subcutaneous haematoma occurred after treatment in four cases, all of which resolved spontaneously within two weeks. Mild abdominal pain occurred after treatment in two cases and disappeared within 12 hours. Two patients caught a cold during the treatment period, which was deemed unlikely to have been related to acupuncture. There were no significant or major adverse events.

4 DISCUSSION

Low-frequency EA has been used to improve reproductive dysfunction 17-19, although the exact underlying mechanism of action remains unknown. Acupuncture has been shown to modulate the sympathetic nervous system as well as the endocrine system and neuroendocrine systems20-21. Acupuncture is believed to affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis by modulating central β-endorphin production and secretion, thereby influencing the release of hypothalamic gonadotrophin releasing hormone and pituitary secretion of gonadotrophins, in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) 22. A similar mechanism may be responsible for the apparent effects of acupuncture in DOR, however further research is required to elucidate the precise effects and mechanisms of acupuncture for reproductive dysfunction.

The aim of the study was to examine whether acupuncture could improve ovarian reserve and thereby increase the chances of pregnancy for DOR patients planning a family. The results showed that mean FSH levels (a key marker of ovarian reserve) decreased significantly at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 24. Differences were also demonstrated in E2 and LH levels at weeks 12 and 24, respectively. Our results are comparable to those of previous studies in POI11-14. Similar influences of acupuncture on FSH, LH and E2 levels have also been observed in studies of PCOS23, menopausal symptoms and other gynaecological conditions24, indicating that acupuncture can modulate reproductive hormone levels and improve ovarian reserve. In addition to the FSH, LH and E2 levels, we examined changes in FSH/LH ratio, an important reproductive marker in some diagnostic criteria25, albeit no longer part of the Rotterdam criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS26. The FSH/LH ratio demonstrated a similar downward trend to the individual FSH and LH levels, culminating in a significant difference compared to baseline at week 24. Based on the observation that differences in FSH and LH levels, FSH/LH ratio and irritability score at week 24 (i.e. 12 weeks following completion of treatment), acupuncture may ha[]ve a long-term effect on hormone levels and emotion. Such long-term effects have also been observed in other studies 11-12. Regarding menstruation, no significant differences were demonstrated in cycle length or blood volume, although this might represent the fact that menstrual symptoms were mild in the sample we observed.

Unlike in other studies, measurements were also taken 4 and 8 weeks of treatment herein, at which point FSH (but no other outcome measure) changed significantly. It was unclear whether this effect was related to the small sample size or the limited treatment duration. In support of the latter assumption, it has been reported that 10-14 weeks of treatment needs to be administered before changes in ovulation frequency are observed in PCOS patients 26-27. Interestingly, the FSH level seemed to be more easily affected by acupuncture than the other parameters.

In order to fully interpret our results, it must first be acknowledged that there is variability in the methods used to diagnose DOR across clinics, states, and regions. In China, the FSH cut-off for the diagnosis of DOR is usually ≥10 and <40 mIU/ml [14]. However, Barad et al. have suggested that FSH thresholds for the diagnosis of DOR should be age specific: >7.0 mIU/ml for patients <33 years of age; >7.9 mIU/ml for those aged 33–37; and >8.4 mIU/ml for those aged 38–40 28. In this study, we used the Chinese FSH cut-off because it is stricter, thus all patients diagnosed using a >10 threshold also met the criteria proposed by Barad et al. Regarding the symptom scale, considering that most DOR patients in our clinic have emotional symptoms rather than somatic symptoms (sweating, flushing, etc.), we used a two-item emotional scale instead of a more heterogeneous measure such as the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS). Most previous trials on ovarian reserve in DOR have been conducted by reproductive centres and outcome measures have included pregnancy rates, antral follicle count and levels of inhibin B, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and/or FSH10,29-30. Although AMH appears to be superior to FSH as a marker of ovarian reserve, especially among older women 31, we did not use it due to funding considerations. We chose instead the (change in) FSH level as our primary outcome as this is still considered to be a robust marker of ovarian reserve, however we have commenced a controlled trial using AMH as an outcome measure, which is now at follow-up stage.

This study has some further limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, as it is a single group observational study, the lack of the control group unfortunately means that we are unable to quantify the contribution of potential placebo effects and thereby confirm any specific effects of EA for DOR. Randomised controlled clinical trials are needed to determine the efficacy (relative to sham) and effectiveness (compared to the best available treatment) of acupuncture for this condition 22. Cooperation between TCM hospitals and reproductive centres is likely to be beneficial for planning such a trial in China. Secondly, patients receiving EA were ultimately seeking an increased chance of pregnancy via IVF or natural conception. Although we demonstrated a significant effect on hormone levels, this are ultimately only surrogate markers. By completion of 24 weeks follow-up, four of 25 patients (16%) had fallen pregnant and were therefore not included in the final analysis. We did not extend the follow-up further to observe the pregnancy rate among the remaining patients, therefore the impact of EA on conception remains unknown and requires further investigation.

5 Conclusion

EA may decrease FSH and LH levels and FSH/LH ratios, increase E2 levels and improve emotional symptoms in patients with DOR without significant side effects. These effects appeared to last for at least 3 months following completion of treatment.

References

[1] Levi AJ, Raynault MF, Bergh PA, et al. Reproductive outcome in patients with diminished ovarian reserve[J]. Fertil Steril, 2001, 76(4):666-9.

[2] Scott RT, Jr, Hofmann GE. Prognostic assessment of ovarian reserve[J]. Fertil Steril, 1995, 63:1–11.

[3] Pal L, Beviacqua K, Zeitlian G, et al. Implications of diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) extend well beyond reproductive concerns[J]. Menopause, 2008,15(6):1086-94.

[4] Chen Lixia. The clinical and empirical research on the effect of the Zi Gui Huo Xue Yi Jing Recipe on the peri-POF Period[D]. Guangzhou, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine,2007:8-15.

[5] Chen Lixia, Li Yanhua, Liang Xiaoyun, et al. Influenece of Jianpi Yishen method on the ovarian reserve[J]. Chinese Journal o Clinical Research, 2013, 26(1): 73-74.

[6] Cizmeli C, Lobel M, Franasiak J, et al. Levels and associations among self-esteem, fertility distress, coping, and reaction to potentially being a genetic carrier in women with diminished ovarian reserve[J]. Fertill Steril, 2013, 99(7):2037-44.

[7] Loutradis D, Drakakis P, Vomvolaki E, et al. Different ovarian stimulation protocols for women with diminished ovarian reserve[J]. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2007, 24(12):597-611.

[8] Narkwichean A, Maalouf W, Campbell BK, et al. Efficacy of dehydroepiandrosterone to improve ovarian response in women with diminished ovarian reserve: a meta-analysis[J]. Reprod Bio Endocrinol, 2013, 16(11):44.

[9] Norbert Gleicher, David H Barad. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation in diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) [J]. Repriductive Biology and Endocrinology, 2011, 9:67.

[10] Yingchun Z, Fangyuan L, Lanrong L et al. Influence of acupuncture and herbs for ovarian reserve[J]. Journal of Sichuan of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2010, 28(12):103-104.

[11] Kehua Zhou, Jingxi Jiang, Jiani Wu, et al. Electroacupuncture Modulates Reproductive Hormone Levels in Patients with Primary Ovarian Insufficiency: Results from a Prospective Onservational Study[J]. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013,657234.

[12] Yingru Chen, Yigong Fang, Jinsheng Yang, et al. Effect of Acupuncture on Premature Ovarian Failure: A Pilot Study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Wang, Li Yang: Effect of Acupuncture on Premature Ovarian Failure: A Polit Study[J]. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014, 718675.

[13] HE Wen-yang. Acupuncture for 15 premature ovarian insufficiency patients[J]. Zhongguo Zhenjiu, 2000,7:399.

[14] SHA Gui-e, ZHAO Wen-min, MA Ren-hai. Observation of acupuncture for 76 premature ovarian insufficiency patients[J]. Zhonguo zhenjiu, 1999, 34: 653-656.

[15] J. Cohen, Chabbert-Buffet, Darai. Diminished ovarian reserve, premature ovarian failure, poor ovarian responder-a plea for universal definitions[J]. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2015, 32:1709-1712.

[16] XU Xiao-feng, FAN Chun, BAO Guang-qin, et al. Investigation on the Factors Related to Premature Ovarian Failure and Diminished Ovarian Reserve[J]. Chin J Evid-based Med, 2011, 11(4):400-403.

[17] Stener-Victorin, E., Waldenstrom, U., Tagnfors, U.,et al. Effects of electro-acupuncture on anovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome[J]. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 2000, 79(3): 180–188.

[18] Gerhard, I., Postneek, F. Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of female infertility. Gynecol[J]. Endocrinol, 1992, 6: 171–181.

[19] David Carr. Somatosensory stimulation and assisted reproduction[J]. Acupunct Med, 2015, 33:2-6.

[20] He J, Yang L, Qing Y, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on bone mineral density, oestradiol level and osteoprotegerin ligand expression in ovariectomised rabbits[J]. Acupunct Med, 2014, 32(1): 37-42

[21] Elisabet Stener-Victorin, Xiaoke Wu. Effects and mechanisms of acupuncture in the reproductive system[J]. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical, 2010, 157:46-51.

[22] Stener-Victorin, E., Jedel, E., Manneras, L. Acupuncture in polycystic ovary syndrome: current experimental and clinical evidence[J]. J. Neuroendocrinol, 2008, 20: 290–298.

[23] J. Johansson, L. Redman, P. P. Veldhuis et al. Acupuncture for ovulation induction in polycystic ovary syndrome: a ran- domized controlled trial[J]. American Journal of Physiology— Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2013, 304(9): E934–E943.

[24] Sunay D, Ozdiken M, Arslan H, et al. The effect of acupuncture on postmenopausal symptoms and reproductive hormones: a sham controlled clinical trial[J]. Acupunct Med, 2011, 29(1):27-31.

[25] Lejie. Gynecology[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2008:308.

[26] Hulia Johansson, Leanne Redman, Paula P. Veldhuis et al. Acupuncture for ovulation inductionin policy stic ovary ayndrome:a randomized controlled trial[J]. Am J Physilo Endocrinol Metab, 2013, 304:E934-E943.

[27] Jedel E, Labrie F, Oden A, et al. Impact of electro-acupuncture and phys- ical exercise on hyperandrogenism and oligo/amenorrhea in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 300: E37–E45.

[28] Barad, D.H., Weghofer, A. Gleicher, N. Age-apecific levels of basal follicle stimulating hormone assessment of ovarian function[J]. Obstet. Gynecol, 2007, 1404-1410.

[29] Shawn E. Gurtcheff, Nancy A. Klein. Diminished ovarian reserve and infertility[J]. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2011, 54(4):4666-667.

[30] Barad DH, Brill H, Gleicher N. Update on the use of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation among women with diminished ovarian function[J]. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2007, 24:629-634.

[31] Barad DH, Weghofer A, Gleicher N. Comparing Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) as predictors of ovarian function[J]. Fertil Steril, 2009, 1553-1555.

世界针灸学会联合会

世界针灸学会联合会